Overview

Seven black men in total were murdered by white lynchers during October 9-11 1878. Daniel Harrison Sr. , Jim Good, William Chambers, Edward Warner. and Jeff Hopkins, who were all brutally lynched in front of the courthouse on October 11, 1878. Two sons of Daniel Harrison Sr., Dan Harrison Jr. and John Harrison, were murdered by lynchers during the days that preceded the courthouse massacre. Some contemporary accounts identify the three dead Harrison men as having the surname “Harris.” As noted below, I think it possible that the man identified as “Edward Warner: was in fact “William Edwards.”

—Jeff Hopkins,

—Daniel Sr Harris (Harrison) and his sons Daniel Jr and John

—Jim Good

–the question of Ed Warner or William Edwards

—William Chambers,

As we shall see, descent lines are clear for Jeff Hopkins and the Harris/Harrison extended family; the family histories of Jim Good, Ed Warner (William Edwards?) and William Chambers are somewhat less clear.

____________________________

The Family of Jeff Hopkins

Jeff Hopkin was lynched by hanging in front of the Posey County Courthouse on October 11, 1878. Moments before his murder, he affirmed his innocence and emphasized that he had a wife and five children.

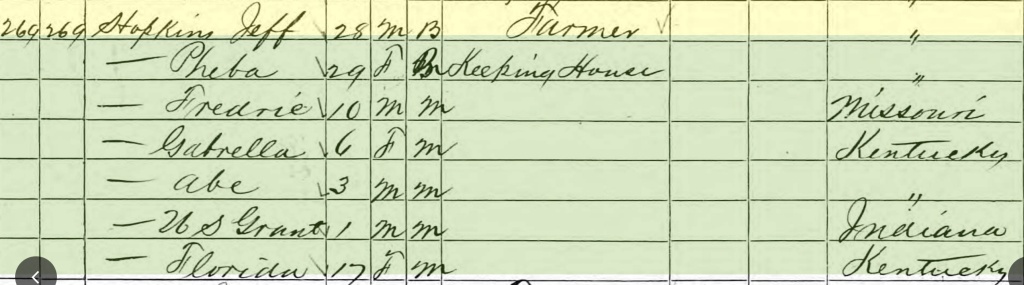

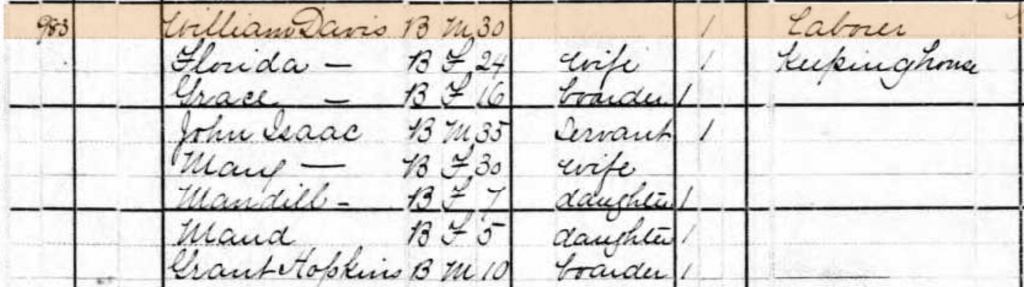

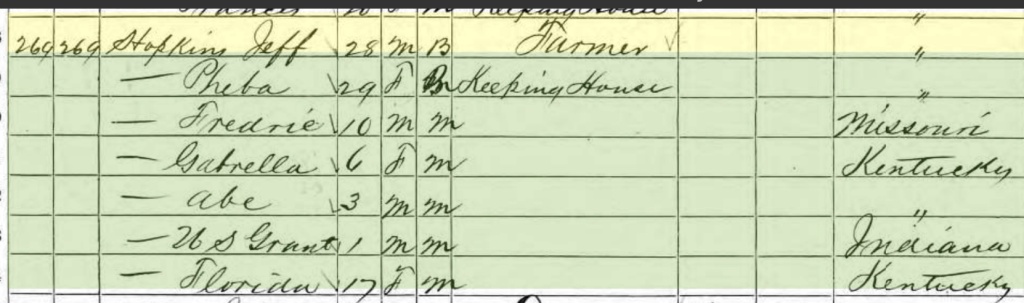

Jeff Hopkins appears in the 1870 census living in Black township, Posey County, Indiana; he is born in 1842 in Kentucky and married to Pheba Hopkins, born in Kentucky in 1841. He resides with their son Fredric Hopkins, born 1860 in Missouri; a daughter, Gabrella Hopkins, born 1864 in Kentucky; a son Abe Hopkins, born 1867 in Kentucky; a son, US Grant Hopkins, clearly named for the Union General Ulysses S. Grant, born 1869 in Indiana.

1870 census, Black township, Posey County, IN. Family of Jeff and Pheba Hopkins

Also living in this household is the 17 year old young woman Florida Hopkins, born 1852 in Kentucky. Given the ages listed it is possible that Florida is a daughter of Jeff and Pheba Hopkins, or perhaps she is Jeff’s sister. She might perhaps be the enslaved female child born in 1855 in Washington, Kentucky, the property of Wilson H. Jones, listed in state records.

Note: In a different post I discuss the possible slavery background of Jeff and Pheba Hopkins.

We should note that of these minors, Florida, Fredric and Gabrella were probably born in slavery, while Abe and US Grant were born in freedom. The location and ages would suggest that the Hopkins family came from Kentucky into Posey County, Indiana at some point after 1867, when Abe was born, and before 1869, when US Grant was born.

According to the 1880 census, none of the surviving members of the Jeff and Phebe Hopkins household were residing in Posey County two years after the lynching. For understandable reasons, they appear to have vacated the county. The only black person remaining in the county with the surname Hopkins is Dick Hopkins, born 1853 in Kentucky, residing in 1880 in Lynn township, Posey County, listed as a servant in the household of the white woman Jane Stallings. Perhaps he was kin to Jeff Hopkins.

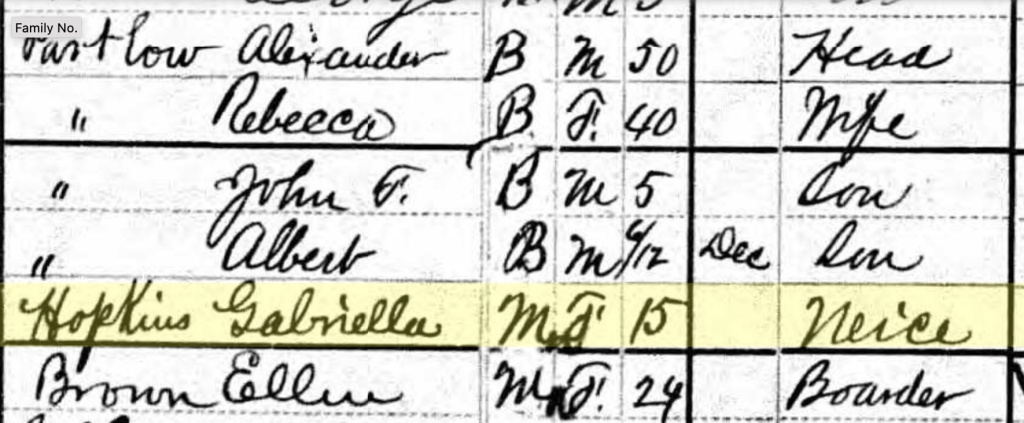

At least five Hopkins family members by 1880 resided in the city of Chicago. 280 miles north of Mount Vernon. According to the 1880 census, Jeff and Pheba’s daughter Gabriella Hopkins resides at 1433 State Street, in the household of Alexander Partlow (listed in 1880 as born Tennessee, but according to later records born in Lake Saint Joseph, Tensas Parrsh, Louisiana) and his wife Rebecca (born Kentucky). Alexander Partlow or Pardlow had married Rebecca Jenkins in Chicago on 10 Jun 1874. Garbriella is listed as the ‘”niece” of the household head Alexander. Since Gabriella’s parents Jeff and Phebe were both born in Kentucky, it seems reasonable to surmise that Rebecca Jenkins Pardlow was the sister of either Jeff or Pheba. It seems likely that after the lynching, Rebecca invited her nieces and nephews to come to Chicago from Mount Vernon.

Rebecca Jenkins Partlow dies 30 May 1888. Her death records indicates she was born in Boyd County, Kentucky, in the northeastern corner of the state, about 300 miles east of Posey County, Indiana. She is buried in Oak Woods Cemetery, Chicago. Her husband Alexander dies seven months later, 2 Jan 1889, and is also buried in Oak Woods.

According to the the 1910 census, Alexander and Rebecca Partlow have two sons, John F. age 5, and Albert, four months old, who must be Gabriella’s cousins, either through her mother or father. John Fredrick Hamilton, a musician, married Harriet “Hattie” Hamilton on 2 November 1897, He died in 1906. It is not clear if the couple had children.

In turn, Albert Partlow married on 20 Dec 1905 to Anabell McAbee. He worked as a laborer in a warehouse and died 31 May 1920. The couple had two children, Elmer Parlow (b 1907) and Earl Partlow (b. 1908). I have not yet traced their descendants.

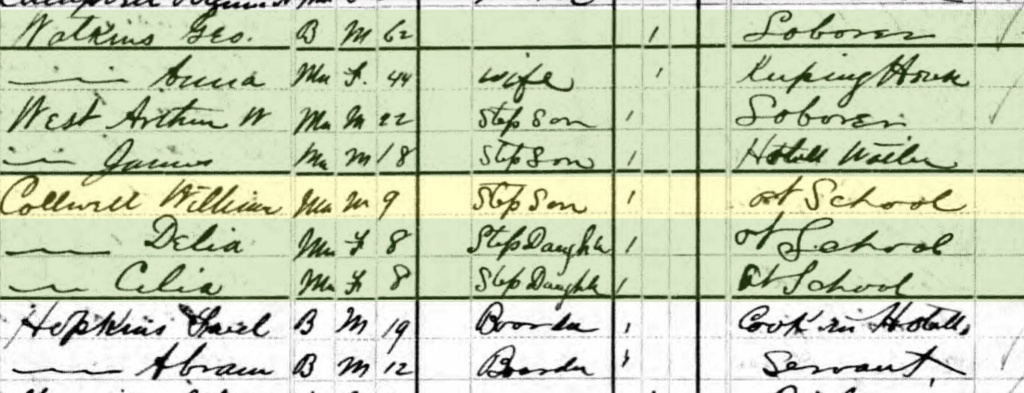

Returning to the 1880 census, four blocks away from the home of the Partlow’s and Gabriella Hopkins, Gabriella’s brother Fredric Hopkins and Abram Hopkins, reside at 1813 State Street, as boarders in the household of George Watkins, a black laborer. Fred, employed as a waiter in a hotel, is listed as suffering from dropsy (edema); his 13 year old brother Abraham is employed as a servant.

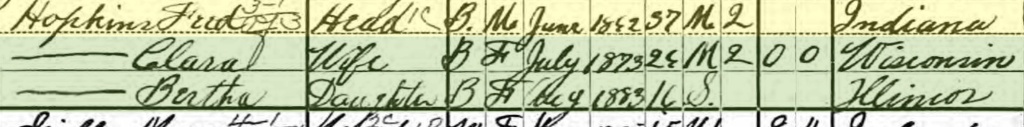

Three years later, on 23 July 1883, in Chicago, Fred Hopkins, residing at 2125 Clark St, marries Mary Sheedy. On 20 June 1898, Fred marries Clara Yancy. In 1900, Fred is at 2528 La Salle St, Chicago, working as a teamster. His wife Clara Hopkins, is listed as born in Wisconsin. Fred has a 16 year old daughter, Bertha Hopkins, by a previous marriage or relationship with a woman born in Ireland, perhaps Fred’s first wife, Mary Sheedy, who may be deceased at this point.

On 31 December 1901, Bertha Hopkins (the daughter of Fred Hopkins) married John B Stobbal, a teamster, who died in 1909 in Chicago. I do not see a record of the couple having children. I am not sure what became of Bertha Hopkins Stobbal, the grand-daughter of Jeff Hopkins.

On 21 Nov 1906, Clara and Fred Hopkins had a son, Albert Hopkins, also listed as Alfred, The child died age 13, on 26 Jan 1919. The child’s death certificate, it is interesting to note, records Fred Hopkins as born in Mount Vernon Indiana, and Clara as born in Beloit, Wisconsin.

The 1923 city directory records Fred Hopkins as residing at 4318 Evans Street, Chicago, on the South Side and working as a salesman for a grocery store. His wife Clara is listed as a laundress for a private family. Fred dies 11 August 1932, and is buried in Thornton, Cook County, Illinois. It is interesting to note that in his death record, his mother’s name is recorded as “Rebecca.” Presumably, this is a reference to his aunt Rebecca Jenkins Partlow, who may have helped raise him after he and his siblings made their way to Chicago after the lynching of their father.

The Chicago death records also records Fred’s sister, “Gabrella Hopkins” as living at this same address, 4318 Evans, Chicago (in the North Kenwood neighborhood of the South Side). She is listed as daughter of Jeff Hopkins, died in Chicago on 9 August 1929 and was buried 13 August in Mt Glenwood Cemetery, Thornton, Cook County, IL. Her occupation is listed as housework. Her birth place is recorded as “Mount Vernon, Illinois,” which must be a slight mistake. At this same address, 4318 Evans, as noted. above resides Fred Hopkins

Gabrella is not listed in the 1923 Chicago city directory. However, a black “Gabriella Hopkins” resides in 1922 at 303 Chesterfield in Nashville, Tennessee, working as a domestic, according to the city directory. Perhaps she returned late in life to Chicago to reside with her brother Fred and sister in law Clara.

Fred’s widow, Clara Hopkins, in turn, appears in the 1950 census as a widow, in Chicago. It does not appear that Clara and Fred had a child other than Albert. They thus may not have left behind any descendants.

Returning to the ,1880 census, when Fred and Abe Hopkins were living at 1813 State street, two other Hopkins family members were living nine blocks away, at 963 State Street in downtown Chicago. They resided in the household of a black man, William Davis (b. 1850, Missouri). The former Florida Hopkins is now William Davis’ wife, “Florida Davis,” born about 1856 (that is to say four years older than the Florida Hopkins listed in the 1870 census). Also residing in this household is Grant Hopkins, age 10 (born about 1870), born in Indiana, with a listing that his father was born in Kentucky. This boy must be the same person as the one year old named “US Grant Hopkins,” the youngest son of Jeff and Phebe Hopkins, in the 1870 census in Mount Vernon. Although listed as a “boarder,” he must have been taken in by Florida, who must be either his aunt or elder sister.

Grant Hopkins, laborer, born 1870, dies 30 November 1888, at age 18, at St. Luke’s Hospital, and is buried at Oakwood Cemetery; this seems likely be “our” Grant Hopkins, youngest child of Jeff Hopkins.

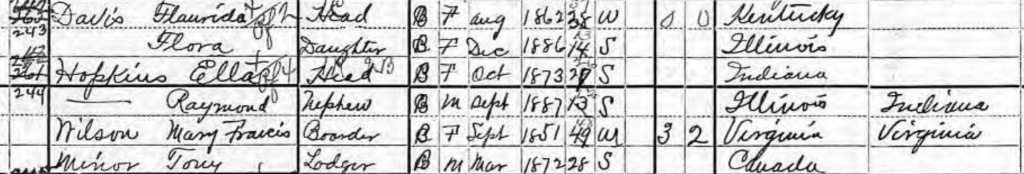

Grant’s sister or aunt Florida (Hopkins) Davis does seem to appear in the 1900 census, as the widowed “Flaurida Davis,” residing at 456 60th street, Chicago. She is listed as born in Kentucky (with her mother also born in Kentucky) in 1862 (that is say a good deal later than the listings in the 1870 and 1880 censuses,) She is living with her 14 year old daughter Flora Davis, born in Illinois in December 1886.

. It is interesting that living adjacent to them, according to the 1900 census, in the same house number is an Ella Hopkins, a single women born in Indiana in October 1873, with her nephew Raymond Hopkins, born in Illinois in September 1887, It seems likely that Ella Hopkins is somehow kin to Jeff Hopkins.

Flora Davis evidently married Stanley Tarver (b. 1899 in Indiana), a cooper in a barrel factory, in the early 1920s; she lived until 1959. Through their son Stanley James Tarver (1925-1997), Flora and Stanley have multiple descendants, many of whom are still alive.

I have not yet been able to trace Phebe Hopkins, the widow of Jeff Hopkins; Given that the death record of Fred Hopkins lists his mother’s name as “Rebecca,” an evident reference to his aunt Rebecca Jenkins Partlow, it seems a reasonable inference that Phebe died soon after the lynching, and that responsibility for raising the children fell to Rebecca and Florida Hopkins.

The Harris (Harrison) Family

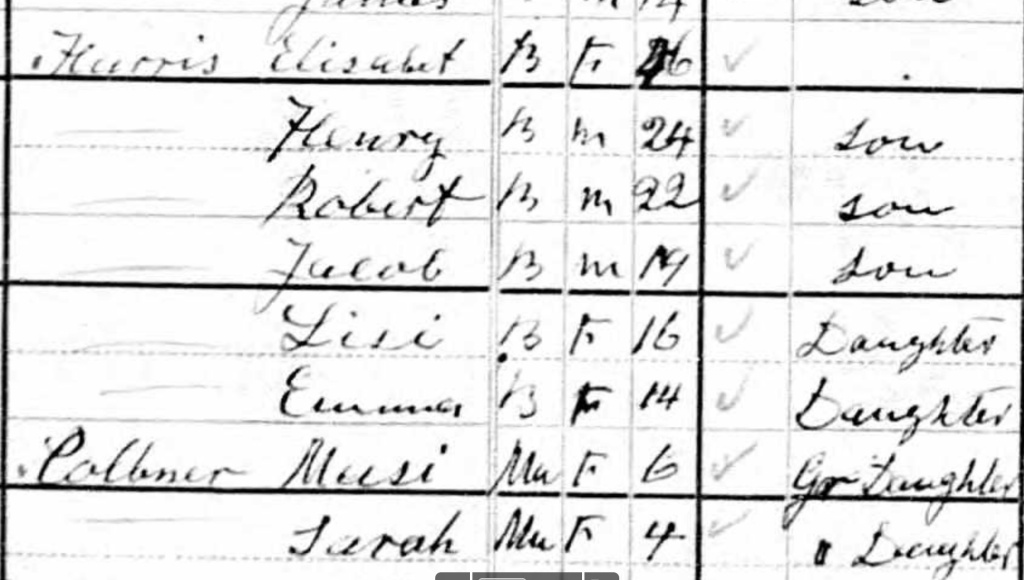

Contemporary newspaper accounts reference the father and two sons killed in October 1878 as either having the surname “Harris” or “Harrison.” The 1870 census lists no “Harrisons” in Posey County in 1870, but residing in Black Township, Mount Vernon, Posey County, about eight households from Jeff Hopkins was Daniel Harris, age 33 (born about 1837), married to Elizabeth Harris, age 31, with children Jane, 18, Nicy, 16, John H, 14, Roberts 12, Daniel 11, Jacob 9, Elizabeth 5, Emma 4, and Fannie, 1. (According to one contemporary account Daniel Sr stated, just before his death, that he was married with eight children.) The fact that his daughter Elizabeth Harris was born in 1865 in Kentucky, and the next child, Emma, was born in Indiana in 1866, suggests that the family likely moved to Posey County just after the Civil War. (As noted below, circumstantial evidence suggests that the family may have come from the vicinity of Morganfield, Union County, Kentucky, about 20 miles south of Mount Vernon).

On the night of October 10, James Redwine asserts, burned alive in the furnace steam engine of a railroad train locomotive, after he attempted to escape his killers by hopping a train. When armed white men came to seize his brother John on the night of October 10, their father Daniel Harris, Sr. resisted by shooting a shotgun.. Daniel Sr. was wounded in the encounter and then later his body was hacked to pieces by the lynch mob at the courthouse. .

The fact that in October 1878 Daniel Harris Sr. capably defended himself with a shotgun when he was attacked in his home might suggest he had military training. It may be significant that several African American men named Daniel Harris served in the Union Army during the Civil War. One enlisted in Chattanooga TN and served in 44th US Colored Infantry (Co. D), Another served in the 8th US Colored Infantry, Co. D. (Two other men named Daniel Harris served in the 32nd and 52nd US Colored Infantry, respectively, but but both died of disease in the service. )

1880 census, Evansville, IN for Julia Harris and children Celia and David Harris.

1880 census, Evansville, IN for Julia Harris and children Celia and David Harris.The 1880 census, enumerated two years after the lynching, shows that the widowed Elizabeth Harris has moved her family 20 miles east to Evansville, Indiana, residing at 23 Franklin Street (p. 30 in the census). Some of the children seen in 1870, Robert, Jacob, Lisl (Elizbeth?), and Emma, are still residing with her, joined by a son Henry, age 24. Jane and Nicy, however, are missing. The household also consists of two granddaughters of Elizabeth Harris, Musi (?) Colbner, age 6, and Sarah Colbner, age 4, both listed as mulatta. The two granddaughters are presumably related to Fredrick Colbner (born Germany 1822) and his wife Elizabeth Colbner (b. 1828, Germany) who in 1860 resided in Black township, Mount Vernon, Posey County, Indiana, the same township in which the Harris family resided in the 1870s. In the 1860 census, the Colbners had two sons Fredrick and Jacob, and it is possible that one of them married (or had a liaison with) a daughter of Elizabeth and Daniel Harris, perhaps Jane or Nicy, and that Musi and Sarah thus bear his surname.

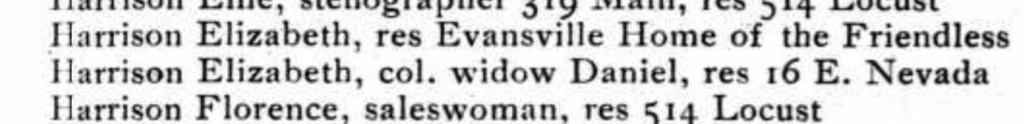

In reference to the confusion of the names “Harris” and “Harrison”, it should be noted that the 1880 Evansville City Directory lists Elizabeth “Harris,” as a widow, but that the 1882 Evansville City directory lists Elizabeth’s surname as “Harrison, “still residing at 23 East Franklin, listing her as a “widow.” In turn, the 1895 Evansville city directory, lists, “Elizabeth Harrison, col, widow of Daniel,” “as residing at 16 E Nevada in Evansville.

By 1910, Elizabeth Harrison is once again living in Mount Vernon, with her son Robert Harrison and his children. It is possible, that like many other African Americans, she had fled Evansville after the notorious July 1903 massacre (the so called “race riot’).

Children of Daniel Harris Sr and Elizabeth Wagner Harris (Harrison)

What became of Jane Harris. daughter of Daniel Sr and Elizabeth Harris, born c. 1852, who is listed as a mulatta in the 1870 census? I see two possible candidates:

(1) According to the 1880 census, a Jane Butter, born 1852, widowed, is residing in Evansville, with her “mother” Gabrilla Harris. and infant daughter Georgette Butter, in the household of Jane’s “sister” Mildred Dunega, who must be Gabrilla Harris’s daugther, residing at the rear of 412 3rd Avenue, Evansville.

Ten years earlier, according to the 1870 census, most of this Harris family was residing in Morganfield, Union County, Kentucky., about twenty miles south of Mount Vernon, in the household of the white woman Margaret (Davis) Berry (the widow of Peter Davis) and her son John, a druggist. Gabrilla Hopkins is listed with her daughters Mary, age 18, and Nancy 10. Millie Dunegan is listed with her daughter Amy, age 3. There is no reference to a Jane.

In 1860, the late Peter Berry (who died 22 April 1869) owned 29 slaves in Morganfield, Union County, Kentucky, In 1850, he had owned 19 slaves. It seems quite possible that Gabrilla and her daughters were all enslaved on the Berry plantation, and continued to work for the Berry’s after emancipation.

I am unsure where the name “Butter” might come from: there was a George Butter, a white butcher, residing elsewhere in the county during the period, so perhaps infant Georgette was named for him.

In his book, Judge Lynch, James Redwine asserts that at some point in Mount Vernon prior to the lynching, an illicit affair took place between Daniel Harris Jr and a married white woman, Sarah Jones, resulting in the birth of a little girl, and that Daniel Jr.’s sister Jane Harris (whom he described as nearly passing for white) agreed to raise her niece as her own child. I am not sure what evidence Redwine has for this, since his book is structured as a historical novel and is not clearly sourced. A\

If Redwine’s account is correct, it may be that Jane and the baby were at some point moved to Evansville to reside with Gabrielle Harris, whom told the census enumerator that Jane was her daughter.

(That may suggest that Daniel Harris came from the Union County, KY area. As it happens, the 1860 slave schedule lists multiple slaveowners with the surname Harris in Union County; so it is possible that Daniel and Elizabeth Harris were enslaved by one of these slaveowners. Only one of these, Addison Jefferson Harris, has slaves in 1850 who are identified as mulatto, which may be significant. The Harris plantation was in District 2 of Union County, the same district as the Berry Plantation referenced above.

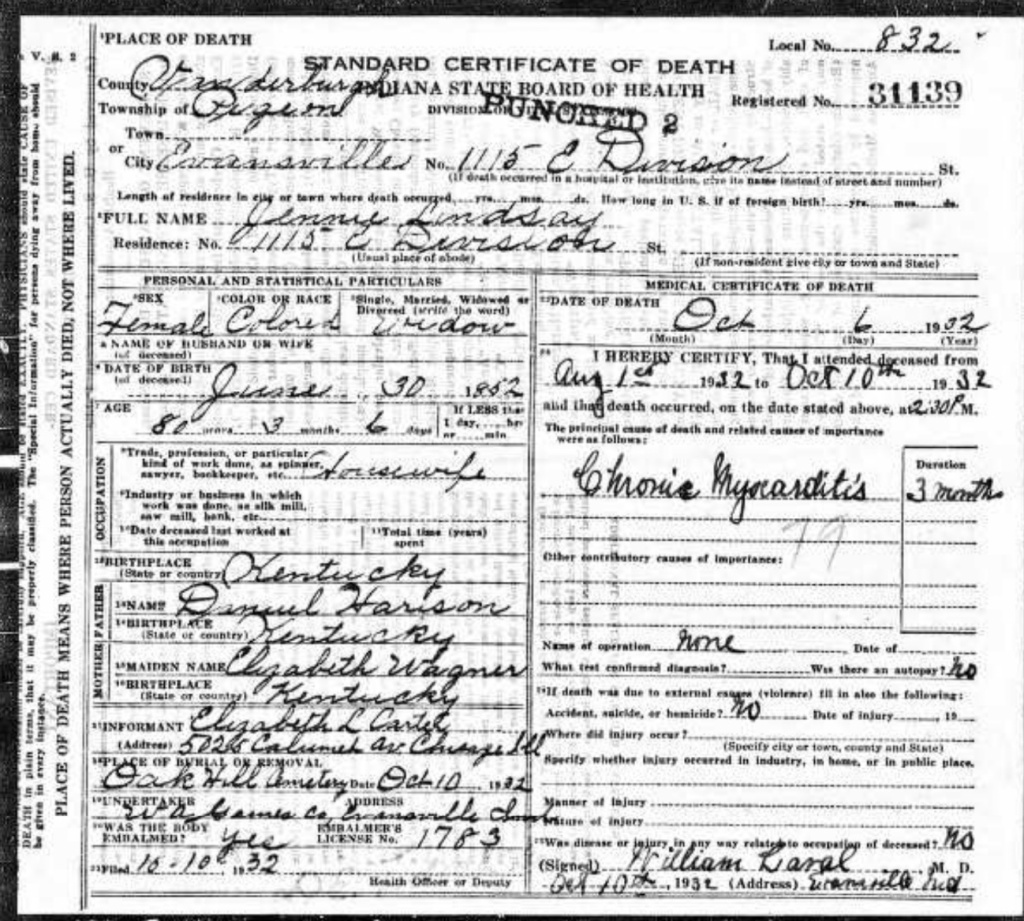

2. An alternative possibility for Jane Harris in the 1880 census is the woman identified as “Jennie Lindsay” (b 1852-d. 6 October 1932 enumerated in Evansville (p. 1) in the 1880 census. Her 1932 death certificate in Evansville, Indiana identifies her parents as Daniel Harrison and Elizabeth Wagner. She married Thomas Lindsay around 1870.

The children of Thomas and Jennie Lindsay include:

Mayme Lindsay, b. 1873-d, 27 October 1945 in Evansville. She married James R. Porter, and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Mary Lindsay Smith , born December 1873. By 1900, she was widowed, having lost her only child, and was living with parents on Williams Street.

Robert William Lindsay, born 10 July 1876. In 1910 he was residing with his wife Minnie, his mother Jennifer, and his sister Elizabeth (Mons). His World War I draft registration card lists him at 2330 Calumet in Chicago IL., laboring in the stock yards. He died 24 April 1929 in Chicago and is buried in Mt Greenwood cemetery. His death certificate indicates his mother Jennie Harris was born in Louisville, Kentucky.

Daniel Lindsay, born 1880, d. 21 Nov 1910 in Evansville.

Lucy Lindsay, b. 1883

Julia Lindsay, b. Sep 23, 1884-d. 1937. Her first husband was Nathaniel Coates in Evansville, Indiana. She later took the married name Watson. By 1930 she resided in Chicago, with her children Jennie, Charles, Tom and Rudolf. Jennie later married Thomas Wilson.

Elizabeth Lindsay Carter, b. 30 Jun 1888.

The 1895 Evansville City Directory lists Thomas Lindsay, colored laborer, as living at 503 1/2 Williams Street, along with his son Robert W. Lindsay, also a colored laborer. His daughter Mary Lindsay, a teacher, boards at 602 Cherry. The 1910 city directory for Evansville records siblings Robert, Daniel, Lucy, and Julia LIndsay also residing at 932 Cherry. (Robert must have moved to Chicago soon afterwards)

Among Jennie Harris Lindsay’s distinguished descendants was the noted artist and arts instructor, Fred Robert Wilson (1937-2012) See his 1990 ceramic head sculpture at: https://romaarellano.com/listing/690163089/1990-raku-pottery-face-vase-by-fred (And there is a moving video on his pottery teaching techniques.) Fred Robert Wilson’s son Andre Wilson, an accomplished poet and prose writer, has written brilliantly on family narratives of racial violence and performed works based on ancestral stories about Jenny’s childhood during slavery times. In another post, I discuss one of these performance piece, The Story of the Black Cat.

Returning to the other children of Daniel Sr and ELizabeth Harris or Harrison, the 1900 census records Robert “Harrison”, born December 1858, at 1211 Harrison Street, Mount Vernon, IN, who is clearly the same person as Robert Harris, the son of Daniel Sr and Elizabeth Harris. Employed as a laborer in a brickyard, he resides with his wife Maggie (Margaret Robinson), whom he married in 1883, and with their children Elizabeth, age 17, Eugene, 14, Robert, 12, Homer D, 7, Owen D, age 5. The same family is recorded at the same address in the 1910 census, now joined by Robert’s mother, listed as “Elizabeth Harrison”, widowed, born Kentucky around 1840. So after some years away from the town where her husband and two sons were lynching, Elizabeth evidently made the decision to return to Mount Vernon., perhaps because of the trauma of the Evansville massacre of 1903 By 1920, however, Robert Harrison, his wife Elizabeth, their daughter Emma F, their grandsons Vernon, Emmanuel and Alfred, and mother Elizabeth Harrison were all residing in Danville, Vermillion County, Illinois.

Robert and Margaret Harrison’s daughter Blizabeth B (“Lizzy”) Harrison died,of pneumonia, in Mount Vernon on 2 March 1904, at age 20, and is buried in the Mount Vernon Emancipation Cemetery. Although buried under the name Harrison, her death certificate lists her as married under the surname Bradbury, which might be a married name, although a husband is not listed.

Robert and Margaret son Robert Harrison Jr, born 7 July 1887, in Mount Vernon. His 1917-18 World War I registration form records him living at 528 Johnston St in Danville, Illinois, working as a railroad track labor. He is single and the sole support of his six year old son. The 1930 census shows him working as a laborer for a fertilizer company. married to Ella Harrison, living at 1502 Arnold Street, Chicago, IL , with children Mae, age 5, Lazzieh, age 4, Elmer, age 1, and Eugene, 4 months. Robert Harrison died in Chicago, 13 Dec 1937.

The 1940 census records Robert’s widow Ella Harrison residing at 1133 Wentworth Avenue, Chicago Heights, Bloom township, Cook County, Illinois, with her daughter Bertha (perhaps the same person as Mae in the 1930 census?), son Lazzira (?), son Elmer, daughter Eugene, son Arnold, and daughter Arba Della (?), age 3. The 1950 census shows the family in the same address, now joined by grandsons Ernest and Otis.

According to the 1940, and 1950 censuses Robert and Margaret Harrison’s son Eugene Harrison is working as a night watchman, single, in Los Angels, California, never having married. He dies 24 May 1956 in Los Angeles.

In turn, Robert and Margaret’s son Owen David Harrison, born 2 December 1894 in Mount Vernon, was a veteran of both World War I and World War II. In the Second World War, he enlisted on 15 August 1942 and served as a 1st Sergeant in the US Army. The 1950 census lists his wife as Hazel Harrison but at the end of the life, there must have been some concern over the legality of their union, since at age 73 he received a marriage license to wed Hazel Augusta Kiowa on 12 August 1967 in Yavapai, Arizona. He died the next day, in the V.A. Hospital.

As we continue to try to reconstruct the family histories of the seven men brutally lynched in October 1878 by white vigilantes in Mount Vernon, Posey Couny, Indiana, I have been curious about the family background of James (Jim) Good. As previously noted in my overall discussion of the descendant lines, James Good in Posey County, Indiana married Emily Hensley in January 1875. Two years after the lynching, the widowed Emily married Civil War veteran Frank Odem in 1880; the couple remained in Posey County for the rest of their lives.

I think it most likely that the murdered “Jim Good” appears in the 1870 census in Center, Jennings County, Indiana (about 175 miles northwest of Mount Vernon, Posey County, Indiana) as “James L. Good”, born 1857. He is the apparent son of Merrit Good Sr (b. 1815, Kentucky) and Georgiantha Good, (b. 1822, Kentucky). His siblings include:

Warren Good, 1845-1916. b, Kentucky

Randle Bowen, b 1850, Kentucky

Elizabeth (Betty) Bowen, b 1851, Kentucky

Georgiantha Bowen (b. 1853. Kentucky)

Archibald Archy T Goude, (1859-1936, b Kentucky)

William Goude, (who may be the same person as George W Goode) b. 1862, Kentucky

Merrit Good, Jr. b. 1864, Kentucky

Hulbert Good, b. 1865, Kentucky

Since there were no free persons of color with any of the names in Merrit’s famiy in antebellum Kentucky, we may safely infer that this family was enslaved prior to Emancipation. Given that all the children, including Hulbert (b. 1865) were born in Kentucky, we may also infer that the Good family emigrated from Kentucky after Emancipation, at some point between 1865 and 1870, settling in Jennings County, Indiana, across the Ohio River. (The 1870 census records about 220 people of color residing in Jennings County, of whom 150 were born in Kentucky.)

Given that the younger Georgiantha Bowen shares the name of the elder Georgiantha Good, we may speculate that the three Bowens are the children of the older Georgiantha, and that they were fathered by someone other than Merrit Good Sr (who is listed as their father in the 1880 census). As noted below, there is some circumstantial evidence that Georgiantha and/or her children had at one point been enslaved by a slaveowner named Bowen. Perhaps Merrit Sr adopted Georgiantha’s children after the couple married.

Possible Goode Slaveowners

First, let us consider where Merrit Good Sr and his children were enslaved. An intriguing hint is found in the marriage record for James’s brother Archibald Good, born 1859, who on 12 July 1899 in Vernon, Jennings County, Indiana, married Ada Lucinda Lyle (who had previously married, it would appear, a man with the surname Easton). In this record, Archibald lists as his birthplace “Campbellsburg” in Henry County, Kentucky, about 50 miles southeast of North Vernon, Jennings County, Indiana, across the Ohio River.

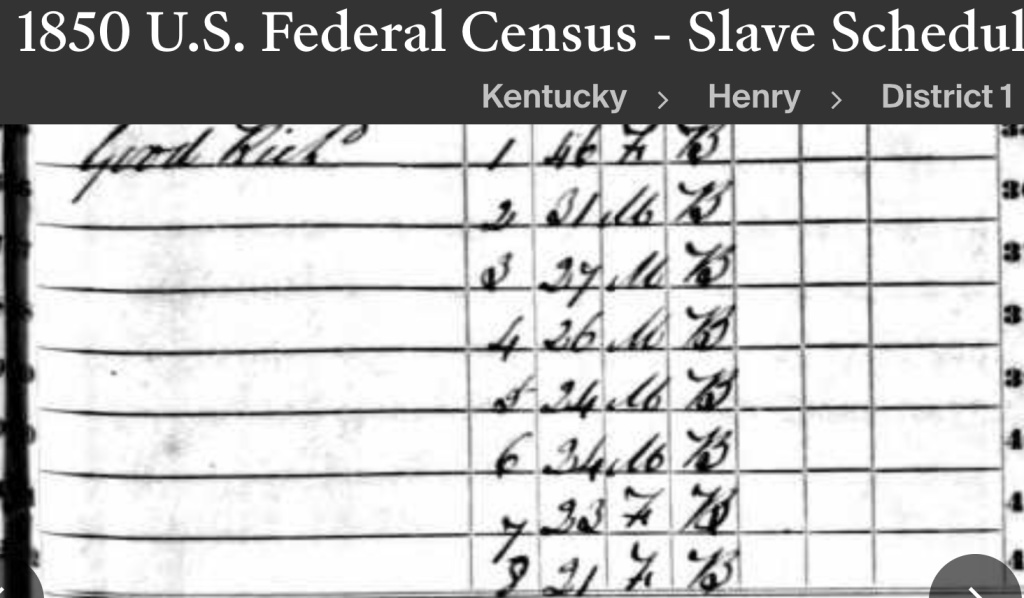

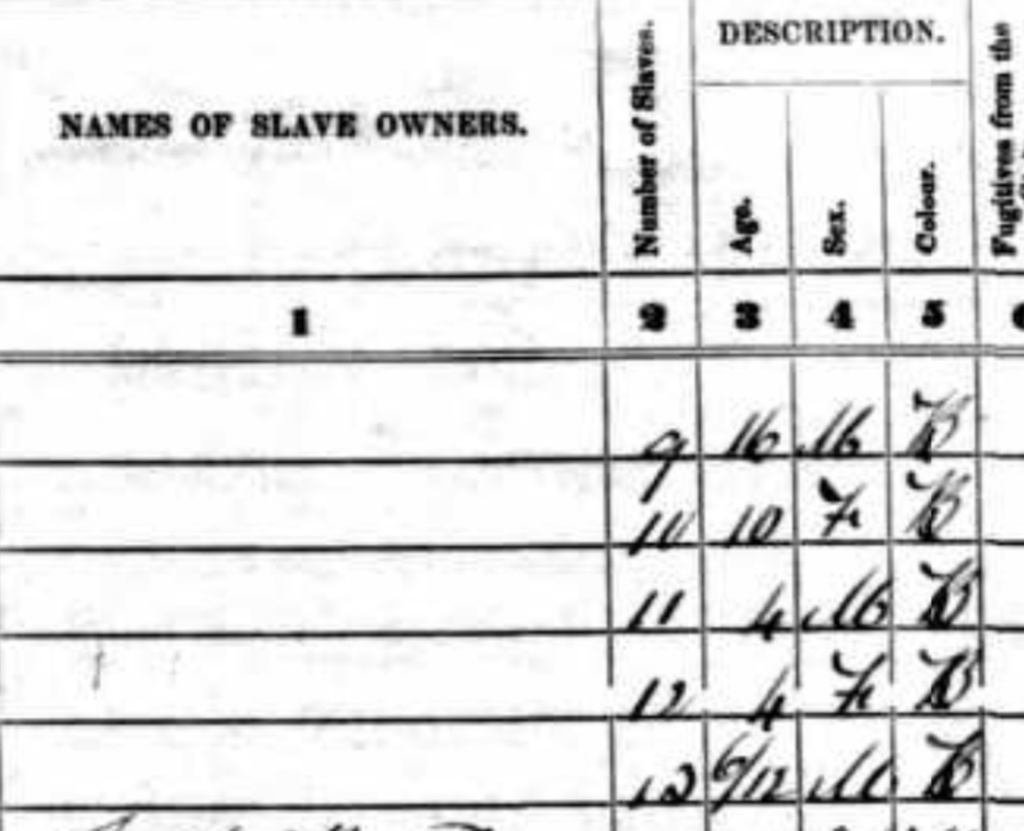

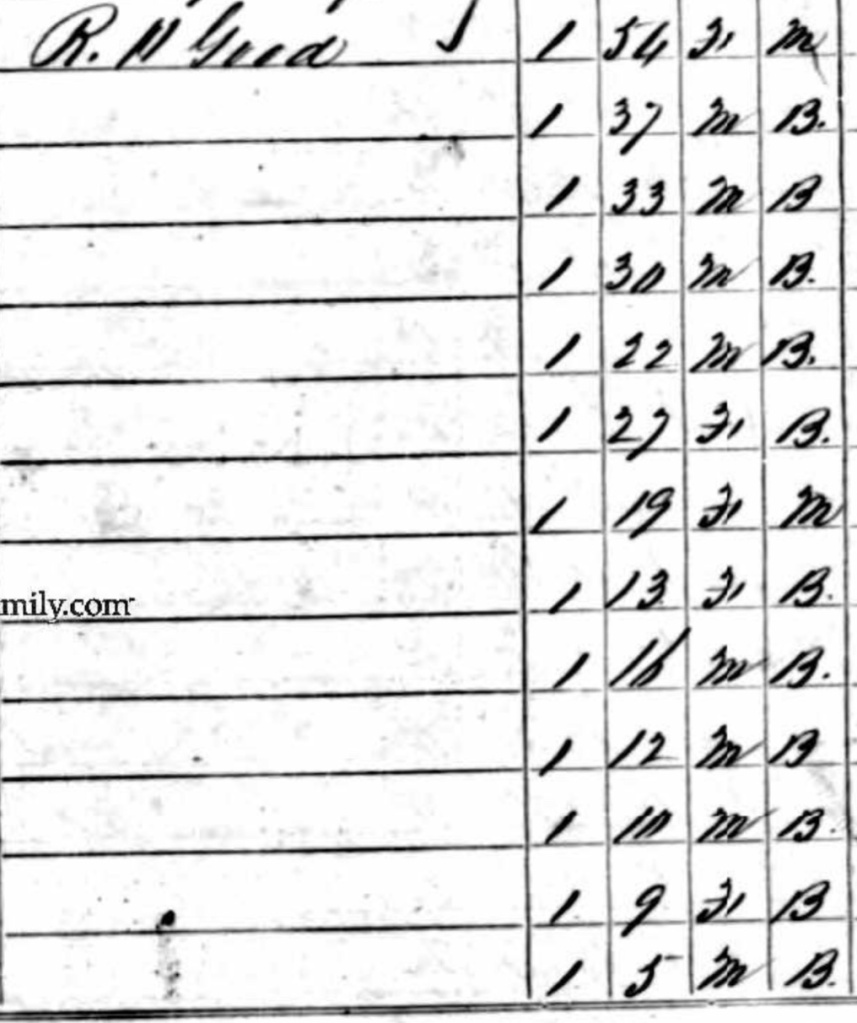

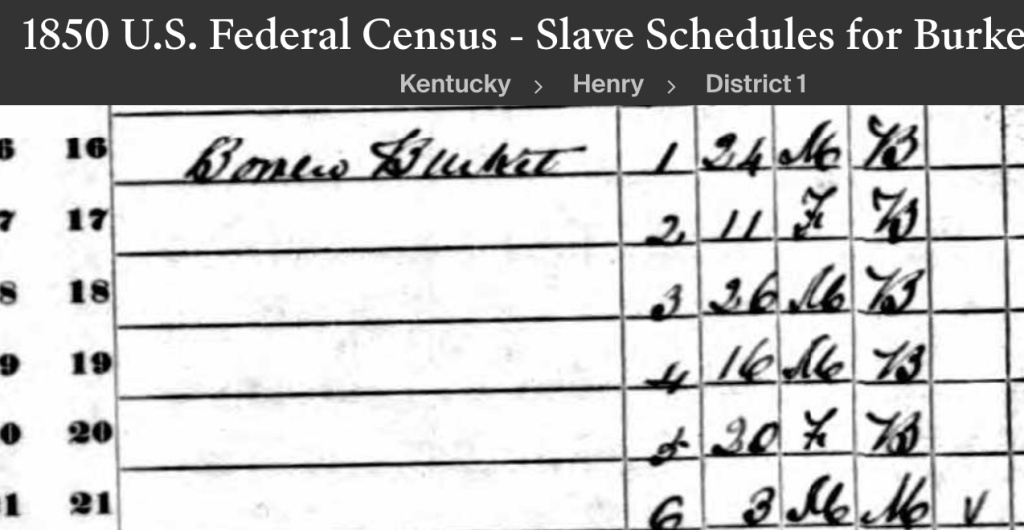

The 1850 slave schedule lists only two slaveowners with the surname Good or Goode residing in Henry County, Kentucky: Samuel or Lemuel Goode (1793-1870) and his brother Richard Young Goode (b. 1795, North Carolina, d. 1873, Sheppardville, Bullit County, Kentucky), who both reside in District 1, Henry County. Lemuel owns 12 slaves and Richard owns 13 slaves. (Matters are a little confusing since Lemuel Good and Richard Young Goode eacg have sons named Richard, born respectively in 1822 and 1824). Richard Young Goode was a veteran of the War of 1812.

Three are several potential matches between the black family of Merrit and Georgiana Good and the slaves owned by the brothers Lemuel and Richard Young Goode, as indicated in the 1850 slave schedules (which records age, sex, and color, but no names). For example,

The 33 year old male slave of Lemuel Good, born 1817, could be Merrit Sr

The 23 year old female of Lemuel could be Georgiantha

The 4 year old male of Lemuel could be Warren

Alternately, the 31 year old male slave of Richard Young Goode could be Merrit Sr

The 4 year old male slave of Richard Young Goode, could be Warren

The 6 month old male, owned by Richard Young Goode, could be Randle Bowen

Ten years later, the 1860 slave schedule indicates that Lemuel Good now resides in McCuistians District, Ballard County, Kentucky (about 275 miles southwest of Campbellsburg, KY) owning four persons:

Male, age 40

Female, age 16

Female, age 12

Female, age 30

Perhaps the 40 year old male, born around 1820, could be Merritt Good, Sr., and perhaps the 30 year old female, born about 1830, could be Georgiantha Good.

The 1860 slave schedule indicates that Lemuel’s brother RIchard Young Goode now resides in District 2, Bullit County, Kentucky, about 60 miles southwest of Campbellsburg, Kentucky, where he owns 16 slaves. Adjacent to Richard Young Goode, “E Good” (presumably Edward Good, the son of Richard Young Good) owns one slave (a 17 year old female) and Richard Good, presumably the son of Richard Young Goode, own one slave (a 30 year old male)

There may be several matches among the slaves owned by Richard Young Goode in 1860:

— a 37 year old male who might be Merrit Good, Sr.

—a 10 year old male who might be Randle Bowen

—a 9 year old female who might be Elizabeth Bowen

—a one year old male, who might be Archibald Good.

It is quite possible that the children had been separated at some point from one or both of their parents.

Possible Bowen Slavowners

Let us now consider the possible “Bowen” connection. It seems quite possible that the wife of Merrit Good Sr, Georgiantha, born around 1822, earlier held the surname Bowen, shared by three of her children (Randle, Elizabeth and Georgiantha), or was owned by a Kentucky slaveowner named Bowen, or that the father of these children was owned by a Bowen slaveowner and used the Bowen surname. The 1850 slave census lists eleven slaveowners named Bowen or Bowens in Kentucky; one of these, Burket Johnston Bowen (1812-1896) , resides in District 1, Henry County, the same DIstrict as both Goode brothers, and lives about 90 households away from Lemuel Goode. In 1850, Burket Johnston Bowen owns six slaves: male, age 24, female age 11, male age 26, male age 16, female age 20, male age 3. There is not a clear match with Georgianatha and her children, but perhaps there is some connection between these enslaved people and her family.

In 1860, Burdett Johnston Bowen is residing in Oregon, Holt County, Missouri, as a wealthy merchant. He does not appear to own any slaves, so perhaps he sold his enslaved property before leaving Kentucky. Speculatively, perhaps one or more of these slaves was acquired by the Goodes, leading to the integration of Good and Bowen families.

Enslaved Persons in Goode family Probate Records

Goode family probate records may provide some hints as to the background of Merrit Good, Sr. Lemuel Good and Richard Young Goode’s father Richard Good VI served as a major in the Revolutionary War, residing in Abingdon, Wythe County, Virginia. After his death from gangrene in 1801 en route to Kentucky, his widow Rebecca Young Goode and her children, including Lemuel Goode and Richard Young Goode, continued to travel with a number of slaves to Kentucky. See:

https://griffintree.tripod.com/id15.html

Richard Good’s will was testated in June 1801 (Henry County Will Book I, p. 17; and in Virginia will records), He bequeaths several slaves to his wife and children:

To Charles Good, my beloved son, a negro boy David

To Susie (?) Good, my beloved daughter, a negro girl Jude

To my beloved daughter Dice (Dicey?). a negro girl Lina (?)

To my beloved daughter Margaret, a negro girl Esther

To my beloved wife Rebecca Good, a negro man by the name Gilbert, a negro man by the name Jesse, a negro woman by the name of Patt, one by the name of Joe (?).

To my beloved son Joel a negro Peter

To my beloved son Samuel a negro Ede (?)

To my beloved son Richard Goode a negro boy named Elas (?)

Rebecca Goode’s will in Henry County, Kentucky, (Henry County Will Records, 1800-1812, Vol. 1, p, 72) in turn references a negro woman Patt and a negro woman Jude who had been bequeathed to her by her late husband Richard Goode for her lifetime (widows normally did not receive full ownership of their husband’s property). She bequeaths Jude to her son in law William Bartlett, the husband of her daughter Dicey. She bequeaths the negro woman Patt and her other slaves and their “increase” (meaning the future children of the females) to her other children.

It is possible that some of the slaves of Lemuel Good and his brother Richard Young Goode,discussed above, were derived from or related to this set of enslaved people.

Please share any information or insights into the early history of the Good-Bowen family dating back to the period of enslavement.

An African American man named Henry Harris, born July 1860, is recorded in the 1900 census, residing at 711 Darnell, Indianapolis, with sons Jim H Harris, 14, and Carey M Harris, 13. This may be the Henry, born about 1856, the son of Daniel Sr and Elizabeth Harris.

The Harris/Harrison Extended Family

Daniel Harris seems to have had kin in the vicinity. In 1870, in Black Township, Mount Vernon, about thirteen households away from Daniel, was residing the African American couple, Reuben and Parnesa (McGill) Harris, both born in Kentucky. They had married in Kentucky, 21 January 1869. Reuben served as a Private in the 88th US Colored Infantry during the Civil War.

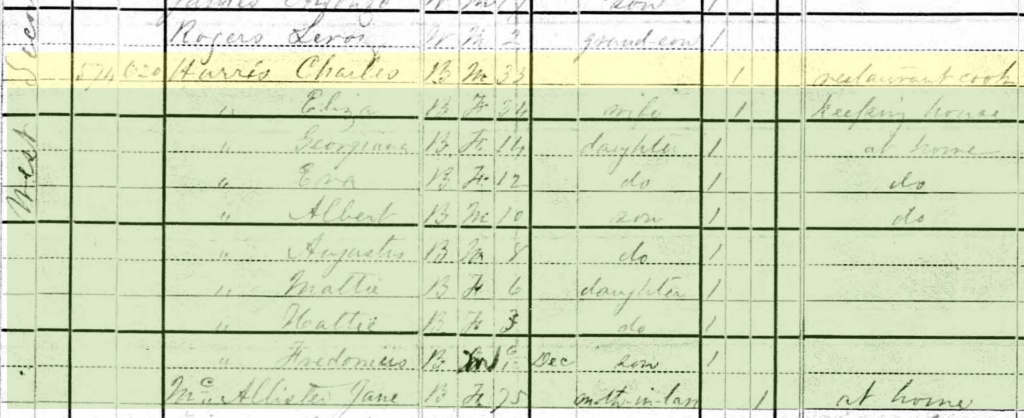

Also, African American man, Charles Harris, born 1847 in Kentucky, married an Eliza Jenkins in Mount Vernon, Posey County, Indiana on 5 September 1867. The couple was still residing in Mount Vernon in 1880, two years after the lynching, with the following children: Georgiana, Eva, Albert, Augustus, Mattie, Hattie, Fredonius. (Redwine in Judge Lynch identifies Charles Harris as the brother of Daniel Harris, Sr.)

Of possible significance, recall that Rebecca Jenkins Partlow in Chicago after the lynching clearly looked after the children of Jeff and Phobe Hopkins. Might she have been kin to Eliza Jenkins Harris, the wife of Charles Harris?

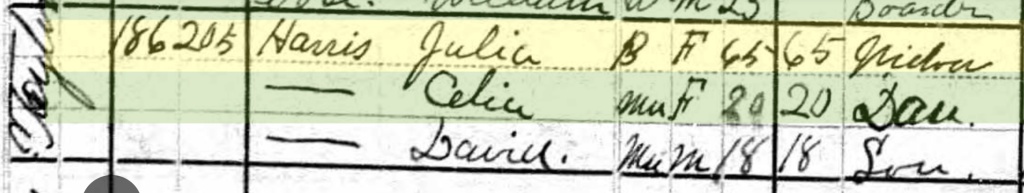

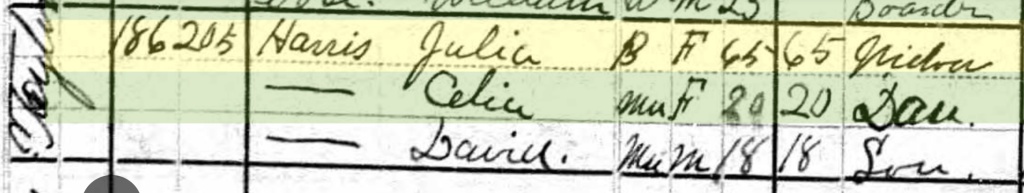

It may be that Elizabeth Harris moved to Evansville, to be close to her late husband’s kin. As noted above, there is some evidence that Gabrilla Harris, residing in Evansville in 1880, was perhaps a sister of Daniel Harris, Sr. The 1870 census records an African American woman, Julia Harris residing in Evansville Ward 2. She is born around 1820 in Kentucky, and is working as a domestic, residing in the household of the black farm laborer Phillip Long. Living with her is 13 year old Celia Harris, her daughter. Perhaps Julia and Celia Harris are kin to Daniel Sr, Daniel Jr, and John Harris?

The 1876 Evansville City Directory records Julia Harris as widow, residing south of Taylor and east of Campbell The 1880 census, enumerated two years after the lynching, records Julia Harris still residing in Evansville, on 179 Taylor Street. (although the 1880 city directory gives the address as 21 Taylor Street). Living with her are her children Celia Harris and David Harris (born 1862, Kentucky). The 1882 Evansville ,city directory shows her and her daughter Celia at 21 Taylor Street. David Harris, coachman, works at 9 Chandler Street. Julia is still at 21 Taylor Street in 1889. David, now a porter, resides at 1014 Upper Road. Julia is still at 21 Taylor Street in 1895. She dies in Evansville on 8 Aug 1898

We now turn to more speculative pathways, involving the three other victims of the murders:

Jim Good

It seems likely that Jim Good or Goode, the first of the four victims to be hanged from a tree in the courthouse square on 11 October 1878, is the same person as the James Good who married Emily Hensley in January 1875 in Posey county, Indiana. I do not know if the couple had any children,

Two years after the lynching, on 27 December 1880, the widowed Emily married widower and farmer Frank Odem, a Black Civil War veteran in Mount Vernon, who served as Corporal in the 14th US Colored Infantry Regiment (Co. F). The 1900 and 1910 censuses record the couple residing in Point Township, Posey County, with her name listed as Emiline. The 1900 census indicates she has had four children, all four still living; the 1910 census records three children born, none still living. (I do not know if any of these children were fathered by Jim Good, or if they had any descendants). Emaline Hensley Good Odem died 14 April 1913 of accidental drowning in the Ohio River,. Her death certificate lists her birthplace and that of parents as Harrisburg, Illinois, about 40 miles southwest of Mount Vernon, Indiana. She may have been born in May 1848 or May 1850; she is buried in the Independent Order of Odd Fellows cemetery in Posey County. Her husband Frank died in a veterans hospital in Washington DC in 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The lynching victim Jim Good would seem to be the same person as James L Good, born 1857 in Kentucky, listed as 13 year old male in the 1870 census in Center, Jennings, Indiana, about 175 miles northeast of Mount Vernon. Evidently the son of Merrit and Georgiantha Good, he resides with his apparent siblings Archy (Archibald), Merrit, Hulbert, Randle Bowen, Elizabeth Bowen, and Georgiana.

[As I note in another post, it appears the Good family had been enslaved in or around Campbellsburg, Henry County, Kentucky, during the antebellum period, by either Samuel (Lemuel) Goode or his brother Richard Goode, with a possible connection as well to the slaveowner Burket Johnston Bowen.]

In the 1880 census Merritt Good and his wife Georgia Good are still living in Center township, Jennings County, with four children (Archebald, William, Betty,Bown, Randle Bowen) and one grandchild (Emma Bowen), the evident daughter of Randle Bowen. Yet there is no sign of James residing in Center or elsewhere in the 1880 census. Young Merrit Jr is also missing.

James L. Good’s brother Randle Bowen, b. 1850 Kentucky, in 1880 is listed in the Merrit Good Sr household as a Blacksmith, widowed. On 18 July 1872 he had married Martha Valentine, a domestic servant, born in Abbeville, South Carolina. As early as 1850, Martha and her parents Samuel Valentine and Caroline Dunlap Valentine are listed as free people of color in Jennings County, Indiana. Martha Valentine Good must have died between 1875 and 1880 since Randle is listed in 1880 as a widower. He is raising Emma Bowen, born 1875. evidently the couple’s daughter. I do not see a clear subsequent reference to Randle or his daughter Emma.

After the 1880 census, I do not see clear references to James L. Good’s sister Elizabeth (Betsy) Randle. After the 1870 census I do not see a reference to his sister Georgiantha Bowen.

Nor, after the 1870 census do I see a clear reference to their siblings Merrit Good, Jr. or Houlbert (Halbert?) Good.

James L. Good’s brother Archy (Archibald) lived the rest of his life in Jennings County, Indiana. On 10 December 1885, he married Elizabeth (Lizzie) Constant, who died 9 June 1898. Descendants recall that Elizabeth Constant brought into the marriage a little girl, Debbie Constant Good, c. 1883-1963, who was adopted by Archibald Good. Debbie Good married Austin Bonds, 1 July 1900 in Lawrence, Indiana, and the couple appears to have had eleven children. One of these was Clifford Bonds (Sr.), 1904-1975, who married Ruby McElwain.

A year after the death of his first wife Elizabeth, Archibald Good married Ann Lucinda Easton (or Lyle) on 12 July 1899 in Vernon, Jennings County. (His wedding record lists his birth place as Campbellsburg, Henry County, Kentucky.) Their daughter Pearl Esther was born 29 March 1900. Pearl Esther Good later married Robert Sadler and lived in North Vernon, Jennings County. until her death 4 Feb 1953; her husband lived there until 1987. It is not clear if the couple had children; Robert Sadler’s obituary mentions him being survived by nieces and nephews.

Another brother of James L. Good (evidently by a different mother) was Warren Good (born October 1845 in Kentucky, died 8 JULY 1916 in North Vernon, Jennings County, Indiana) who married Teresa Johnson. Their children included Charles Goode, 1846-1926; Nellie Good, 1872-1963; Melvin Good, 1872-1963; Frank Good 1877-1934; Joseph Lunsford Goode, 1879-1958; Clarence Goode 1882-1913; and Cara Good, born 1884.

Melvin Good married Ellen Nora Easton (1873-1940). Their children included Carlos Good, b. 1901; Mildred Good, b, 1902, Merrill Vivian Good Coleman, born 1906; Russell Good, b 1909, Oswald Good, b 1910; Bernetta Good, b. 1912.

Miss Merrill Vivian Good (whose married names were Coleman and Frazier) had at least one child, Mr. Melbert A Good, b. 20 MAR 1925 • North Vernon, Jennings, Indiana; d.18 APR 1994 • Seymour, Jackson, Indiana), who retrained his mother’s natal name. Melbert married Pauline Evelyn Booker ( 1925-1986). The couple had at least five children.

Another son of Warren and Teresa Good was Joseph Lunsford Good, 1879-1958, who married Mary Cooper. Their daughter was Edna Maria Goode, 1910-1998, who married Jesse Watkins. Their children including Gayland Watkins, 1931-1995; Jesetta Maria Watkins, 1939-1998; Rosemary Teresa Watkins, 1942-2017, who married Harry Phillip Oldham.

Another son of Warren and Teresa Good was Clarence Good, 1882-1913 who married Ida Taylor. Their children included Donald, Clare, Hazel, Alice, William, Edith, Jay.

________

Ed Warner?

The Indiana State Sentinel (Wednesday, 16 Oct 1878, p. 1) in racist language references “Ed Warner,” as “a young, slim, slouchy looking boy of 21, coal black.” If the age given is correct, then the victim would have been born around 1857.

The 1870 census lists four black men named “Edward Warner,” in the United States:

1, one in Baltimore, Maryland (b. 1848), who also appears in the 1880 census, and can thus be eliminated.

2. one in Iberia, Louisiana (. 1861), who also appears in the 1880 census

3. one in Philadelphia, PA (born 1865), who also appears in the 1880 census

4. one in Chattanooga, TN (b. Virginia, 1862, hence five years younger than the victim described in the Indiana Sentinel). He is not clearly listed in the 1880 census.

The 1870 census also lists a William Warner, born 1856 in Kentucky, listed as attending school and residing with his parents Willis D and Mary R (Elliot) Warner, in Indianapolis Ward 5 in 1870. The couple had married on 21 Oct 1857. He is not evident in the 1880 census.

Of possible significance, the 1880 census lists a widowed African American woman Anna Warner, born c. 1843 in Kentucky, residing with her 16 year old son Richard Warner, a servant, (also born in Kentucky, c. 1864) in Evansville, Vanderburgh County, Indiana, to which, as noted, many Mount Vernon African American families after the lynching. Ann Warner and her son Richard board in the household of Sarah Thompson, mulatto, at 233 Sixth Street; she works as a house cleaner. Anna and Richard are not clearly visible in the 1870 census, so perhaps they had a different surname than Warner at that point. Anna Warner died 7 September 1890 in Evansville, at age 48, and is buried in Locust Hill Cemetery. In 1909, a Richard Warner, “colored”, is listed as residing at 625 McCormick avenue Evansville., in the same household as Fred Warner, a “Colored” teamster and Fred’s wife Jennie.

William Edwards?

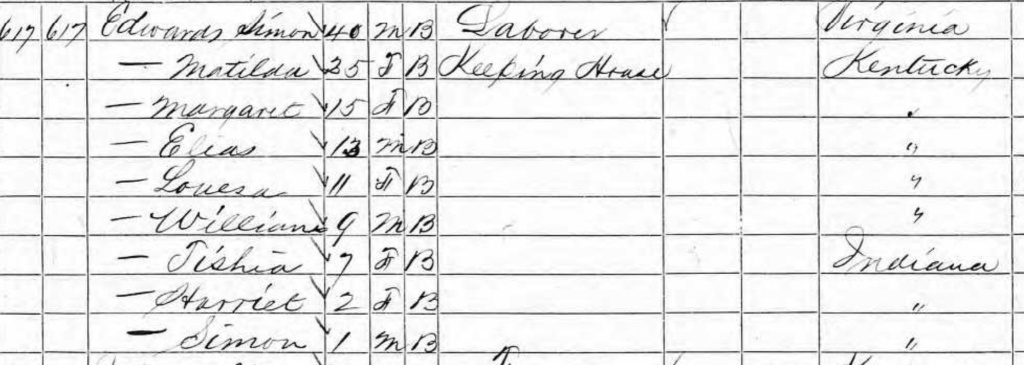

Speculatively, might “Ed Warner” have been misidentified in some contemporary accounts and the recent markers? A highly racist account in The Indiana State Sentinel. 16 Oct 1878, Page 8, refers variously to an “Ed Warner” and a 21 year old man called “Edwards.” Is it possible that the victim was in fact William Edwards, born around 1861, so around 17 at the time of the lynching? In the 1870 census, William Edwards is listed in Black Township, Posey County, the same community as Jeff Hopkins. He is the son of Simon Edwards (1827-21 June 1901), a Civil War veteran who had served in the 8th Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment (Company H), and who married to Matilda Bracknage. William’s siblings in 1870 are listed as Margaret, age 15, Elias, age 12, Louisa, 11, Tisha (Letitia), 7, Harriet, 2, and Simon, age 1.

In the 1880 census (two years after the lynching) Simon and Matilda Edwards and their children are shown having moved about 20 miles northwest of Mount Vernon, to Carmi, White County, Illinois. All the family members from 1870 are still residing in the household, except that William Edwards is missing, and he does not appear elsewhere in 1880 census in the region.

The 1900 census records the family patriarch Simon Edwards, a widower living with daughter Margaret along with his apparent daughter (misidentified as granddaughter) Harriet Edwards, age 30. and grandchildren Ruymel Price, age 20, Mary Walker, age 14 and Ester M Williams, age 4. Next door reside Simon Sr.’s son Simon (b, 1870) with his wife Lucy, and Simon Sr,’s son Elias with wife Maggie.

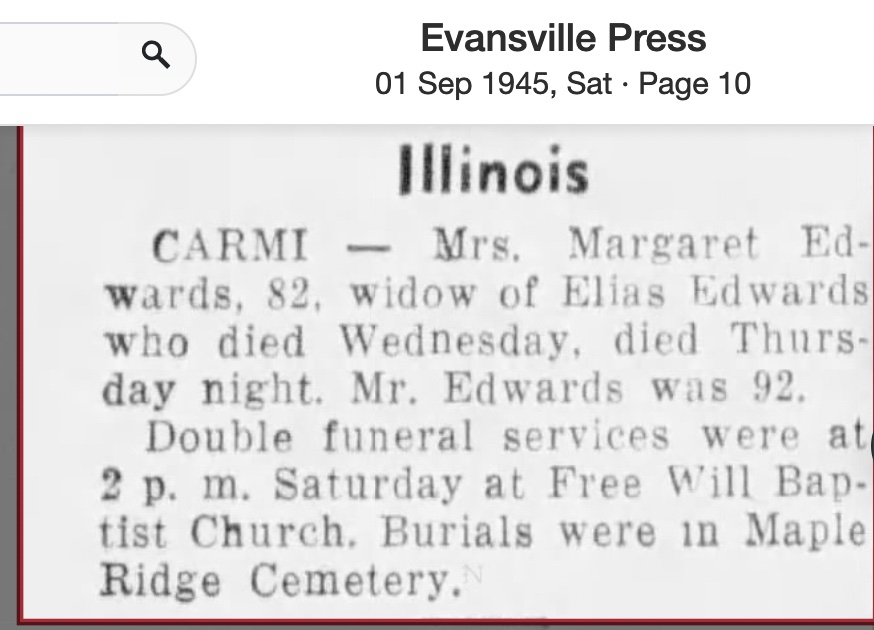

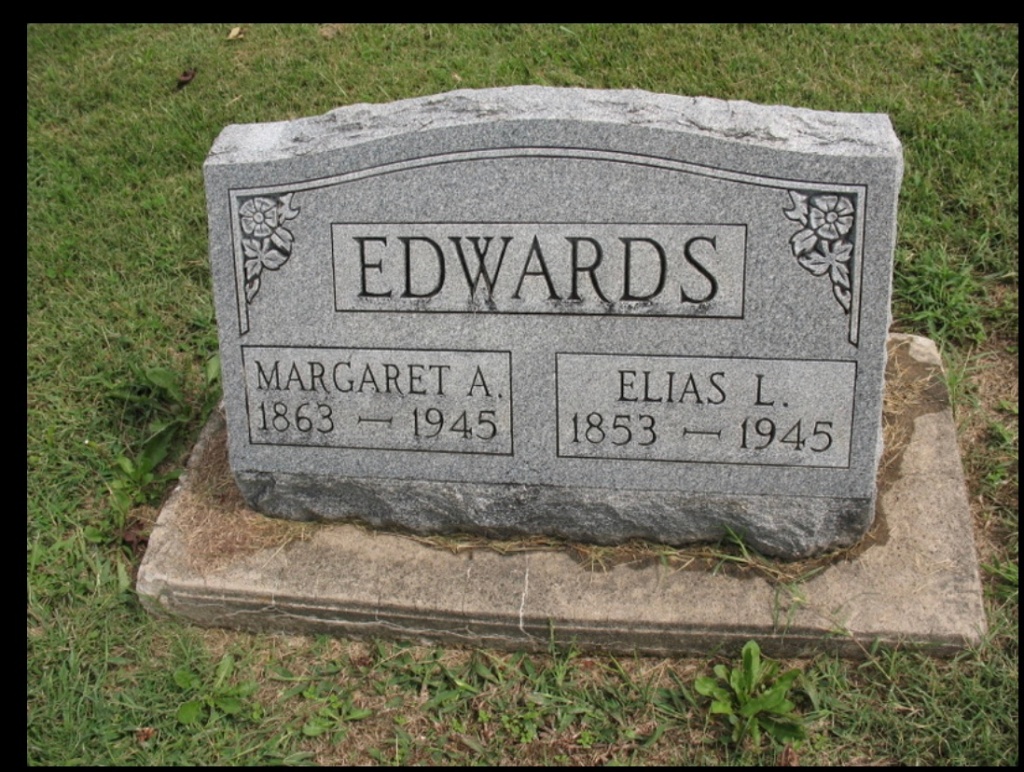

William’s elder brother, Elias Lawrence Edwards, born around 1857, lived the rest of life in Carmi, He married Maggie Ann Ford on 1 Jan 1886. The couple had at least six children, Elias L Edwards, b 1887; Luther K. Edwards, b 1889; Susan Edwards, b. 1891; Emma Edwards, b. 1892, Samuel D. Edwards, b. 1893; Richard Edwards, b. 1898; Clara Edwards, b, 1900; Allie Edwards, b. 1901. These individuals have numerous descendants, including Emma Edwards (Chism)’s daughter, Marguerita Edwards Chism Johnson, a noted educator in Florida who worked extensively on aging issues in Marin County in the San Francisco Bay Area and who earned a doctorate in Mathematics.

Elias Edwards lived until age 92, passing on the last Wednesday of August 1945; his wife Margaret passed away the next day.

Chambers Family

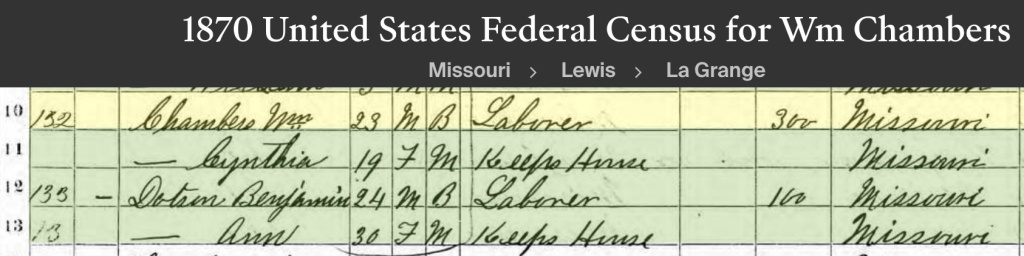

Various newspapers accounts (eg The Evansville Journal, 13 Oct 1878, p. 3: The Farmer and Mechanic, 17 Oct 1878, p. 5) assert that, Bill Chambers was “28 years old” at the time of the lynching, so born around 1850. He is described in the accounts of having “been accused some time since of the assassination of Patt McMullin, a laborer on the government works at Grand Chain, Wabash River,” about ten miles northwest of Mount Vernon. The Evansville Courier and Press, 30 Oct 1877, Tue · Page 4. reports on the murder of a “Pat Mullen,” evidently shot accidentally, in mistaken retaliation, the newspaper speculates for employment having been refused to black men. The Evansville Journal, 02 Nov 1877, Fri · Page 4 reports that five men were arrested for the murder and held in Mount Vernon.

I do not see a William Chambers in the 1870 census in Indiana. About 40 African American men named William Chambers, are listed in the 1870 census nationwide. Perhaps one of these moved to Posey County, Indiana, prior to 1878.

Suggestively residing four houses away from Jeff Hopkins in the 1870 census in Black township, Mount Vernon, Indiana, is the household of the farmer John Chambers (1836-1912), born in Missouri and his wife Ann Chambers (c. 1846-c. 1890) and their newborn girl Francis. During the Civil War, John had served as a Private in Co. F of the First Iowa Colored Infantry. He was the son of Peter N and Phobe Chambers

It seems quite likely that the lynch victim William Chambers was kin to John Chambers, perhaps his younger brother. Given that John Chambers was born in Missouri, it may be that William appears in the 1870 census as a William Chambers in La Grange, Lewis County, Missouri; he had just married, on 15 May 1870, Cynthia Lewis. (I do not see a record of a Cynthia Chambers in the 1880 census, two years after the lynching, and am not sure if the couple had children.)

By 1880, two years after the lynching, John and Ann Chambers have relocated to Fulton, in Callaway County, Missouri, about 260 miles northeast of Mount Vernon, and 100 miles south of LaGrange, Missouri. Their daughter Francis is now joined by her siblings, Ulysses Grant, age 6, Hayes, age 3 and Lillie Angeline, age 2. The fact that all the children, including two year old Lillie Angelina, are born in Indiana would suggest that the family left Posey County after the 1878 lynching, perhaps in flight. However, John clearly maintained ties to Mount Vernon. The Mt. Vernon Democrat newspaper reports on August 18, 1887 that “John Chambers, a very respected colored man of this city, was granted a pension this week.” His wife Ann Chambers died in Posey County, Indiana in 1890. Three years later on 16 March 1893, he married Tilda or Lettie Dixon, in White County, Illinois.

It is interesting to note that a subsequent son of John Chambers was William McKinley Chambers (d. 23 March 1935), who served in World War I. Like John, William was buried in White County, Illinois. (I do not know if this William’s was named for the William Chambers who was lynched in 1878).

Also, of possible relevance, there is an African American Chambers family in 1870 in Evansville, Indiana, about 20 miles away from Mount Vernon The head of household is Alonzo Chambers, age 25 (b. 1845), born in Indiana, married to Mary K. Chambers, age 28. They do not have children in the household with them, but a decade later, in the 1880 census, the have five children living with them: Ida, age 9, Eliza, age 8, Alameta, age 4, Alfred, age 2, and John, one month old. In 1900, the same family is residing in Pigeon, Indiana about 40 miles east of Evansville; the family now includes Moses Chambers (15 May 1899-15 April 1959). Most of these children appear to have lived their lives in the environs of Evansville.

The poet and storyteller Andre Wilson and I have been contemplating how oral historical narratives passed through his father’s African American family about racial terror might be meaningfully compared with textual sources, nearly all of which were created by white authors. Wilson is the great great grandson of Jennie Harris (or Harrison) Lindsey, whose brothers Daniel Harris Jr. and John Harris, were both murdered by lynch mobs on or about October 10, 1878. (Some accounts give the family surname as Harrison or Harison.) Daniel Harris, Sr., who appears to have been Jennie’s stepfather, was, in turn, lynched by a white mob on October 11, 1878, at the Posey County Courthouse Square, in downtown Mount Vernon, Indiana, minutes before four other African American men were hanged by the white mob. The Harris brothers and the four hanged men were accused of having robbed and sexually assaulted three white sex workers; the evidence for these allegations, as has been widely noted, is highly dubious.

Over the years, Andre has collected multiple accounts of a racial terror killing in his family’s history, as told by his father the artist Fred Robert Wilson and his father’s mother Jennie Moore, They relayed stories that had been transmitted by Jennie Moore’s grandmother, Jennie Harris Lindsey, in some cases from eytwitness accounts by her own mother, Elizabeth.

African American oral historical accounts

The core story passed through the black family concerns their ancestor, “Daniel Harris” or “Daniel Harrison,” He is remembered as having come out of slavery with his wife and children, with tobacco seed obtained from his former owner, settling in Indiana. His seven daughters were harassed by a white man in the tobacco fields. Later, this white man sexually assaulted one of them. In response, Daniel confronted the white man, who dared Daniel to kill him. Daniel ultimately did kill the white man. One family account recalls him as “the first black man to kill a white man in the United States.” Following this, a white mob tied Daniel to a railroad car and set it on fire. This brutal murder took place, in one version of the story, in front of Daniel’s wife and daughters.

The various account continue that a group of “Masons” rescued Daniel from the burning rail car, either while he was still alive or after he had died. The Masons then interred Daniel’s body in a secret location, since the white murderers wanted to desecrate his body. In one account, Daniel’s wife was tortured by the white lynchers, but refused to divulge her late husband’s burial location, keeping the secret until the day she died. (In one version of the story, Daniel’s body was rescued and buried by sympathetic Native Americans). Daniel’s surviving family then fled to Illinois, where they continued farming.

So far as I can tell, these oral historical accounts conflate the three murders of the Harris men, a father and his two sons, on October 10 and 11, 1878. [I have earlier suggested that the Story of the Black Cat, passed down in Andre Wilson’s family, might itself be a poetic condensation of the murder of Daniel through fire.]

The precise circumstances of these October 1878 killings of the three Harris men remain somewhat murky. White-authored newspaper accounts assert that on October 10, the day before the spectacle lynching by hanging of four African American on the Posey County courthouse square, the brothers Daniel Harris Jr and John Harris were killed by white men in separate, less public incidents.

James Redwine, a white author who has researched the 1878 lynchings, gives several accounts of the killing of Daniel Harris, Jr. He claims that on October 10 that white killers forced Daniel Jr, whom they had been pursuing on trumped up charges of rape, into the firebox of a steam locomotive, where he was intentionally burned alive. Redwine reports that “Posey County native …Basil Stratton, told me that his grandfather, Walker Bennet, was an eyewitness . Walker told Basil that as a young boy he was present and saw several white men, including Walker’s father, force Harrison into the steam engine. Basil’s grandfather told Basil he never forgot the Black man’s screams and the smell of his burning flesh.” See this account. (Walker Bennett’s father was James Madison Bennett, c, 1826-28 December 1887, a blacksmith who had served in the Confederate Army in the 23rd Battalion, Tennessee Infantry (Newman’s), Company C. )

On the same day, Daniel Jr’s brother John was evidently murdered by white men, and his body stuffed into the hollow of a tree.

The night of October 10, according to Redwine, Daniel Harris Sr, the father of Daniel Jr and John Harris, met an attack on his home by a group of white men with armed resistance. In the exchange of fire, Cyrus Oscar Thomas, 1829-1878, was shot and killed, evidently by Daniel Harris Sr with a shotgun. Daniel Sr was wounded in the firefight and transported to jail. The next day, a white lynch mob attacked the jail and took him into the courthouse square, along with four other black men accused of the rape. The white killers hacked Daniel Sr to death and disposed of his bodily remains in the courthouse outhouse. Minutes later, the white lynch mob hanged the four other men from locusts tree in front of the courthouse.

Cyrus Oscar Thomas was, at the time, evidently running for the office of County Sheriff, and it seems possible that his targeting of black men in these attacks was part of a political strategy for building white support in the upcoming election.

Let us consider in terms the various key elements of the African American Harris/Harrison/Wilson family account, and see how they might match up with or differ from the white-authored texts.

In his book, Judge Lynch, a quasi-novelistic (some might say prurient) reconstruction of the events around the 1878 mass lynching, James Redwine presents Daniel Jr as having a surreptitious sexual affair with a white woman, leading to her secret mixed race daughter being covertly raised by Daniel’s Jr’s sister Jane. This accounts strikes me as highly unlikely. More likely, the possibility of some sort of sexual encounter or encounters between one of the Harris daughters and a white man certainly does seem credible, and is entirely consistent with the racialized sexual politics of the era. It may be that one or both the Harris brothers, Daniel Jr and John, were defending their sister against a white man, and this is what lead to the accusations against them of raping three white prostitutes.

Perhaps Daniel Harris Sr’s shooting of Cyrus Oscar Thomas has been translated or condensed in family memory to the story of his killing his daughter’s rapist. It is certainly possible that the white man that Daniel, Sr shot had in fact assaulted one of the Harris daughters.

In any event, it does appear that the deaths of the two Daniels have been conflated into a single murder in the family accounts.

Redwine’s version, relying on the white grandson of a child eye witness, describes Daniel Jr as having been forced alive into a locomotive steam engine firebox. The African American family account, based on eye-witness recollections by Daniel’s widow and daughters, recalls a railway car being set on fire, with Daniel tied to the burning vehicle.

In both the white and African American accounts, the witnesses presumably were viewing the horrors from a distance, so the precise circumstances of the killing may have been difficult to ascertain. The firebox of steam locomotives had to be large enough for the fireman to rake coals evenly through its floor to create a standardized level of heat to create adequate steam, and needed to be regularly cleaned out, so was presumably large enough to accommodate an adult human body. On the face of it, it seems hard to imagine how the murderers could have forced a strong adult male into the burning fire car without being scorched themselves. In that respect, the African American versions’ reference to a the victim being tied to a burning railcar seem somewhat more credible.

Several iterations of the African American account speak of “The Masons” or a “Masconic Society” coming to Daniel’s aid, either rescuing while he was dying or securing his scorched body once he had died.

There were clearly African American Masons in Posey County, Indiana in the late 19th century. The Western Star newspaper reports African American Civil War veteran Pvt John Tyler Jefferson “died in Mt. Vernon at noon on November 10, 1894. “[H]is remains were interred by the Colored Masons.” (see: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/179094684/john-tyler-jefferson In turn, Purn Dickson Bishop, buried in Emancipation cemetery in Mount Vernon, was a member of Walden Lodge No. 17 of the Free and Accepted Masons and was one of the founders of the Gay Flower Lodge of the International Order of Odd Fellows. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/174074187/purn-dickson-bishop The Mt. Vernon Weekly Republican newspaper reported the Private Jasper Towns helped lead an 1886 initiative to revitalize Mt. Vernon’s Gay Flower Lodge of the International Order of Odd Fellows. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/207419977/jasper-towns

Further north in Indiana, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge, the nation’s oldest African American masonic order, had been present in Indianapolis as early as 1856, and it is possible they also were active in southwestern Indiana in the 1870s.

It seems reasonable that Daniel Harris Sr, who may have been a Civil War military veteran, was a member of a local Masonic Lodge, perhaps the International Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF).

I have not seen any white-authored accounts of a secret burial of any member of the Harris family, although the story is certainly credible. Nor do any of the white accounts reference Elizabeth, Daniel Sr’s widow, being tortured by white vigilantes. I have not encountered grave records of any of the seven victims of the October 1878 lynching, although these may exist.

4. Flight to Indiana.

One of the African American accounts has it that immediately following the lynching of Daniel, the family fled across the Mississippi River to Illinois. Census and city directory records suggest that the surviving members of the Harris family moved to Evansville, in the adjacent county of Vanderburgh, Indiana, and then by 1900 some members, including Daniel Sr’s son Robert Harrision, had returned to Mount Vernon. By 1920, Robert, his wife and children were residing in Danville, Vermillon County, Illinois. Daniel Sr’s widow Elizabeth Harrison died in Danville on 5 April 1920

In this respect, the family story is basically accurate, although it seems have compressed the time between the lynching and the actual relocation to Illinois.

There does not appear to be any photograph record of the remains of Daniel Harris Sr or his son Daniel Jr and John. There is an infamous photograph at the four bodies of the hanging lynched victims. Jeff Hopkins, James Good, William Chambers, and Ed Warner (whose name was perhaps William Edwards), taken on October 11, 1878, in the Robert Langmuir Collection, Rose Library, Emory University. See: https://digital.library.emory.edu/catalog/3246q573t7-cor

The Mt Vernon Dollar Democrat, in October 1878 notes, “Mr. Jones, our artist, took photographs of the four Negroes lynched by the vigilants [sic] last Friday night.It is an excellent representation of the tragic scene.. Mr. Jones has copies for sale.” see https://jamesmredwine.com/1878-lynchings-pogrom/published-in-2005/

The white photographer must have been Leroy William Jones, (29 JAN 1843 -11 JUN 1921) He had a photographic studio in Mount Vernon, IN, from at least 1880 onward. He was a Civil War veteran (Company C, 25th Indiana Infantry Volunteers(. I am sure how many copies of the photograph were made and sold.

Whether or not the murder of Daniel Jr took place in the steam engine firebox or on a burning railroad car, it it is worth nothing how ubiquitous trains, rail lines, rail yards, and rail bridges were in the history of American lynching from the end of Reconstruction onward. Perhaps the most infamous instance is the lynching of Sam Hose in 1899 in Newnan GA in which the local train company arranged for excursion fare for thousands of whites to witness his violent spectacle lynching, an event which arguably led W.E.B. DuBois to quit the South. Rail structures afforded high degree of visibility, and given that one of the core functions of racial terror lynching was to intimidate African American communities, it is perhaps not surprising that rail bridges and rail signal towers were used opportunistically as sites of display of lynched bodies by white perpetrators.

At the same time, the rails were also places of liberation, for those traveling north to the Promised Land in the Great Migration. Railroad employment provided economic upward mobility to Pullman Porters and many others. Yet. there is the dark side of railroad technology,that still casts a shadow to this day, Claude McCay, as a railroad porter who witnessed lynch mobs along rail lines, embodies this ambivalence in writing his poem “If we must die,” calling for armed resistance to white mobs.

Zygmunt Bauman’s book Modernity and the Holocaust, (2013) notes how intimately intertwined the mechanics of mass death during the Shoah were with industrial modernity, including rolling stock and train time tables. A comparable argument could certainly be developed about lynching. Technological triumph and white racial nationalism seem to have been integrally intertwined in many sectors of American society from the end of Reconstruction onward, and this may have overdetermined the horrific use of the railroad apparatus in racial terror.

In our continuing efforts to trace the family histories of the victims of the October 1878 racial terror lynching in Mount Vernon, Posey County, Indiana, what can be determined about the antebellum background of the family of Jeff Hopkins (who was one of the four men hanged in front of the County Courthouse on October 11)? In a previous post, I try to trace the children of Jeff and his wife Pheba Hopkins, who all appear to have relocated to Chicago by 1880. (I have not been able to locate any records of Pheba herself, after the 1870 census entry.)

Let us begin with information listed in the 1870 census in Black Township. Posey County, Indiana, about the Hopkins family.

Jeff Hopkins, b. 1842, Kentucky (farmer)

Pheba Hopkins, b. 1841, Kentucky

Florida Hopkins, p. 1853, Kentucky

Fredric Hopkins, b, 1860, Kentucky

Gabrella Hopkins, 1864-1929, b. Kentucky

Abe Hopkins, b. 1867, Kentucky

Ulysses S Grant Hopkins, b. 1869 Indiana

Evidently, Jeff and Pheba like their children Florida, Fredric and Gabrella were all born in slavery, while Abe and US Grant were born in freedom. Since Abe was born in Kentucky in 1867 and US Grant Hopkins was born in Indiana in 1869, it follows that the family relocated from Kentucky at some point between 1867 and 1869.

Where might Jeff and Pheba Hopkins and their children have been enslaved in Kentucky? It is possible though not a certainty, that Jeff and his family were owned by a slaveowner with the surname of Hopkins, so let us look at Hopkins slaveowners who might have owned Jeff, born around 1842.

In nearly all cases, the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules do not list the names of enslaved persons. However the search functions on Ancestry.com make it possible to limit results based on gender and age.

The 1850 slaves schedule lists about ten Kentucky slaveowners named Hopkins who owned at least one male slave between the ages of six and ten:

James Speed Hopkins (1799-1873) in District 2, Boyle County Kentucky, about 200 miles east of Mount Vernon, Indiana, owned a total of 34 slaves, including four eight-year old males and 2 ten-year old males. His father, John Hopkins, died in Boyle County in 1824. By 1860, James Speed Hopkins had settled in Heaths Creek, Pettis County, Missouri, with 35 slaves, including adolescent male slaves that are consistent with those listed in the 1850 slave schedule, so he can probably be eliminated as the source of Jeff and his family.

In turn, the 1860 slave schedule lists seven Kentucky slaveowners named Hopkins. who own about ten enslaved males between ages 16 and 20 years:

Mary B Hopkins, who owns 31 people (residing in three slave dwellings) in Division 1, Henderson County, about 15 miles southwest of Mount Vernon, Indiana. Her slaves in 1860 include:

18 year old male, who could be Jeff

18 year old female, who could be Pheba

5 year old female, who could be Florida

The identity of this slaveowner is not entirely clear. She seem to be Mary Ann Hamilton Hopkins, married to Edmund Henry Hopkins, who in the 1860 census lists her real estate value as $7,000 (and her personal estate as only $200.) Mary Ann Hamilton Hopkins’s mother Mary Hamilton died in 1861??, and in her will bequeaths one slave Charles to her daughter for the duration of her life, and expresses hope that afterwards he be made a freedman.

Mary Hamilton Hopkins died in 1861. He husband Edmund Henry Hopkins died in 1863.

Curiously, Mary’s appraised estate, on 21 December 1861, only lists one slave, an enslaved man, Harry. valued at $800. The other slaves in her possession were perhaps held on account of one or more heirs to an estate, and do not appear, so far as I can tell, in probate records.

2, An apparently different Mary B Hopkins in Henderson County KY appears to own three slaves in 1860. She may be the daughter of Mary Hamilton Hopkins. This Mary Hopkins, born 1844, in Division 1, Henderson County, seems to have died in 1862.

18 year old male, who could be Jeff

20 year old woman, who could be Pheba

(but no female in the 7 year range)

17 year old male who might be Jeff

18 year old female who might be Phebe

5 year old female who might be Florida

6 month old male who might be Fredric

As noted above, Joseph Haiden Hopkins’ father Samuel Hopkins, who died in 1859, had, in 1850, 20 slaves in Christian County, KY, including an 8 year old male, who could have been Jeff, and an eleven year old female, who could have been Phebe.

The inventory of Samuel Hopkins estate, Christian County Kentucky Probate Records, Will Records, Vol R, p, 152 ff, names about twelve slaves, listed minors as ‘children,’ None of these names correspond with Jeff, Pheba, or Florida, but since they might be kin to Jeff’s family, their names and ages are worth noting:

Christian County KY probate records, vol F p. 156.

Inventory and appraisement of the negroes belonging to the estate of said decedent (Samuel Hopkins)

Silla, about 21 years and 3 children

Killa, 17 years old

Henry, 20

William, 16

Isaac, 28

Daniel, 24

Samuel, 19

Frank, 21

Smith, 43

Wesley, 20

James, 18

Phillis and child, 22

In his will (10 August 1859; Christian County Kentucky Probate Records, WIll Records, Vol R, p. 74.) Samuel Hopkins bequeaths to his grandson Samuel Herndon in Missouri, the slaves Phillis age 20 and infant 18 months old named Willis and a boy seventeen years old Wesley. Phillis and Wesley are married. Also three old negroes Judith (blind), and Isaac and Nancy, who should select which home they will go to. Rest of property to divided up between his children.

———

20 year old male who might be Jeff

22 year old female who might be Phebe, although on the older sisde

3 month old male who might be Fredric

But no female child in the age range for Florida

The widowed Mary Hopkins had been married to Thomas Hopkins, who died 15 July 1858 in Union County, In the 1850 slave schedule Thomas Hopkins in District 2, Union County, KY, owned three slaves:

Female, age 50

Female, 16

Male, 13

Union County Probate Records, Vol E, p 321, from 1858, indicate the following appraisment of Thomas Hopkins’ five slaves:

Negro Woman, Ambigail l(?) valued at $1000

Negro boy Issac 800

Small boy Will, 200

Small Girl Nancy 150

Old woman Hannah (unintelligle) value at 00

Concluding Observations: Of these seven slaveowners, the most likely candidate would seem to be the large slaveowner Mary B Hopkins in Henderson County, KY,, who in 1860 owns three people who more or less match up with Jeff, Pheba and Florida, and who resided relatively near Posey Couny, Indiana.

The next most likely would seem to be Joseph Haiden Hopkins, son of Samuel Hopkins, whose slaves may match up with Jeff, Phebe, Florida and Fredric. His plantation, as noted, was within 100 miles of Posey County, Indiana.

However, as of this writing, I have not come across any probate records of other documents listing the names of the enslaved persons Jeff or Pheba or their children Florida, Fredric, or Gabrella.

I would be grateful for any guidance or suggestions as we continue to seek the early history of Jeff and Pheba Hopkins.

This work is licensed by the David L. Rice Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed by the David L. Rice Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.